It was our first winter on the lake. After years of dreaming, our family finally made the move in December 1984. Among the most excited about our relocation was my father-in-law, John “Pep” Kelch.

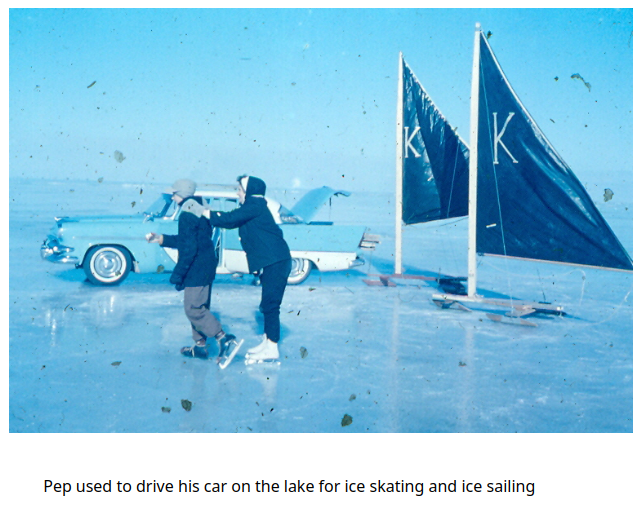

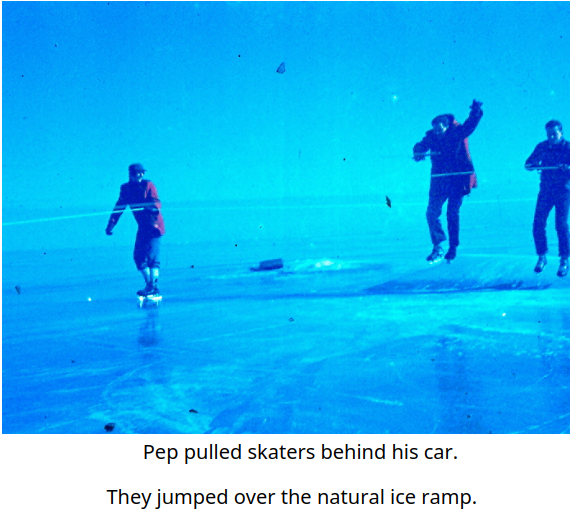

Pep was in his element at the lake. In summer, he was always fishing, swimming, or sailing. But it was winter when his adventurous spirit truly came alive. He loved racing across the frozen lake on his snowmobile, ice fishing with friends, and even ice sailing in the iceboats he built himself.

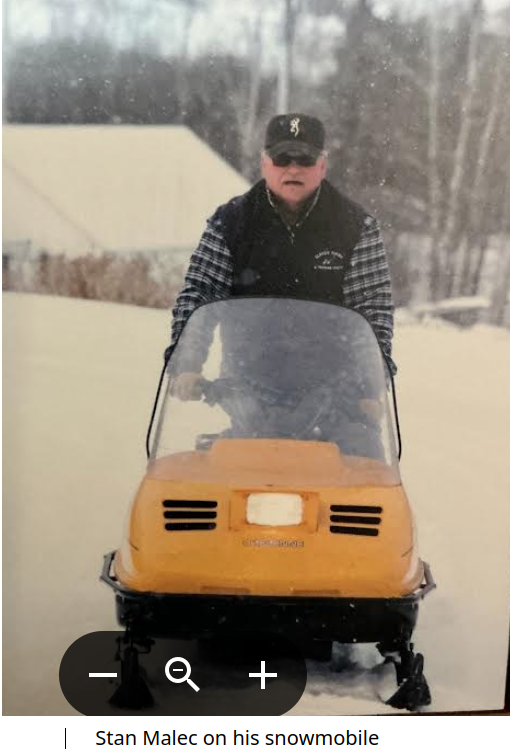

His love of winter sports ran deep. In fact, he had once been featured in the Windsor Star as the first person in Windsor to purchase a snowmobile. It was a 1967 SNO-TREK, and the yellowed newspaper clipping still hung proudly in his garage—a small reminder that he was always ahead of his time when it came to life on the ice.

My neighbour Stan Malec shared Pep’s passion for snowmobiling and ice fishing. One winter day, Stan and his brother Ed planned to go ice fishing on the frozen lake, and Pep was eager to join them. He trailer-ed his snowmobile to our house and set off to meet them on the ice.

By the time Pep arrived, Stan and Ed were already far out—just specks on the horizon. He aimed straight for them. I happened to be at work that day; had I been home, I likely would have gone too.

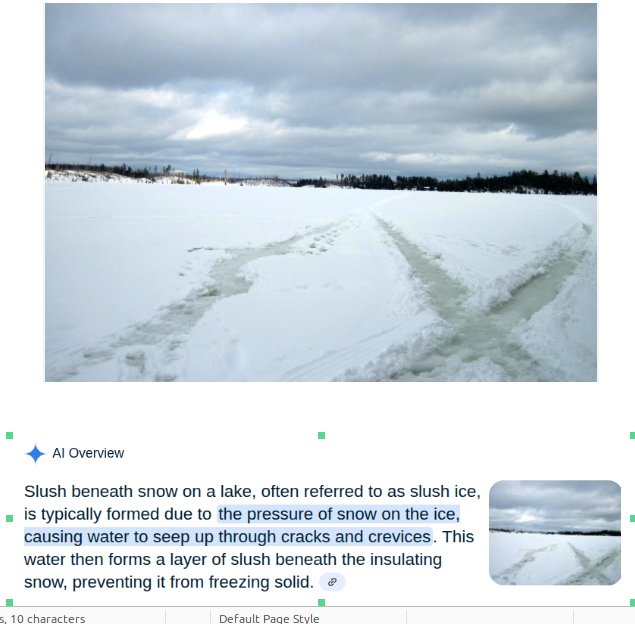

As Pep drew closer, he saw the brothers waving their arms. He waved back cheerfully, not realizing they were warning him of danger. Beneath the snow lay nearly 18 inches of slush. Stan and Ed had just discovered it themselves. Stan’s snowmobile was powerful enough to get out of the slush when they first realized that they were sinking. The key was momentum—you had to skim the surface without slowing.

But Pep slowed down as he approached. His snowmobile quickly bogged down in the heavy slush, unable to regain speed. Within moments, it was hopelessly stuck.

Abandoning his machine, Pep tried to walk the last hundred feet to his friends. Each step drove him through the snow into the icy slush below. His pants were soon soaked, and his movements grew laboured.

“Stay where you are!” Stan shouted. “I’ll come get you. But I can’t stop—I’ll sink too. You’ll have to jump on as I pass by!”

“Okay, I’ll try!” Pep called back.

But when Stan roared past, Pep missed the leap and fell face-first into the slush. Now he was drenched and freezing. Stan circled back, stopping on a firmer patch.

“You’ll have to slog your way to me!” he yelled. “I’ll get you back to shore!”

And so Pep trudged, soaked to the skin and shivering, until he reached Stan’s snowmobile. It was a hard lesson about the lake’s hidden dangers.

Stan wasted no time. He turned toward shore, carefully following a circuitous path to avoid the worst slush. Ed, left behind, watched in disbelief as his brother disappeared with Pep. He felt frustration and even betrayal—why would Stan leave him alone to save an old man who wasn’t even family?

But Stan had made the only choice. Pep was soaked to the bone and already losing body heat. Hypothermia could set in within minutes.

The ride back took nearly half an hour. Fortunately, the snowmobile could drive right up to our side door, which opened into the laundry room. Stan helped Pep inside and, without hesitation, turned back for Ed.

Meanwhile, Pep’s wife Louise and his daughter Cathie sprang into action. Louise stripped Pep’s frozen clothes while Cathie ran a hot bath. Pep soaked for almost an hour, shivering violently at first but slowly warming. Later, he said he had never been so cold in his life.

Back on the lake, Ed waited anxiously for his brother’s return. Minutes stretched into what felt like hours. Worry gnawed at him. Had Stan made it? Did the snowmobile break down? Did Pep even survive?

Finally, unable to wait any longer, Ed tried to walk toward shore. At first, the snow held. Encouraged, he pressed on. But within a hundred feet, disaster struck—his foot punched through into deep slush. Weighted down by the heavy ice auger slung across his shoulders, he sank deeper with every step. Soon his boots and pants were filled with icy water, the freezing wetness creeping upward.

A chilling realization struck him: without help, he wasn’t going to make it. He was now in the same life-threatening situation Pep had barely escaped—except there was no rescue in sight.

Meanwhile, Stan struggled to find his way back. He tried to retrace his earlier route, but the surface was now a maze of crisscrossing tracks. With no GPS, no cell phones, and little visibility in the gathering fog, he relied on instinct alone. He pressed forward through the blinding whiteness, visor fogging, heart pounding.

Then—at last—a speck on the horizon. Ed, waving frantically.

As Stan drew closer, he saw his brother mired in deep slush. He knew he couldn’t reach him directly; if he stopped, he too would sink. Instead, he manoeuvred to a slightly firmer patch and called for Ed to slog his way over.

Exhausted but fuelled by adrenaline, Ed forced himself through the slush, still carrying the heavy auger on his shoulder. At last, he clambered onto the snowmobile.

There could easily have been three fatalities on the lake that day. Thanks to Stan, there were none. Still, Ed never let his brother forget that he had rescued “the old man” first and left him stranded.

Once Pep had warmed up and regained his strength, he dressed and gazed out across the snow-covered lake. He was grateful to be alive—and he knew then and there that he never wanted to go snowmobiling again. The machine that had once brought him so much joy no longer mattered. He phoned his eldest son, Vic, and told him plainly: if he wanted to retrieve it, he could have it.

A day or two later, Vic arrived at our house at dawn. The timing proved wise. A sharp overnight freeze had solidified the slush, making the lake more passable. With a pair of powerful binoculars, Vic spotted the abandoned snowmobile and began the long walk toward it. The plan was risky. If he couldn’t get the machine running, it would be a cold, exhausting trek back on foot.

But luck was on his side. When he reached the snowmobile, he discovered that someone else had already tried—and failed—to salvage it. They had pulled it free of the slush, but when they couldn’t start it and had no way to tow it, they simply left it on the bare ice.

What they didn’t know was that Pep had secretly installed a hidden on/off switch as a theft deterrent. Vic, of course, knew exactly where it was and turned it on. With one pull on the starter rope, the engine roared to life. Moments later, he was riding triumphantly back across the lake.

We were still asleep that morning when we were startled awake by the unmistakable buzz of a snowmobile as Vic circled our house.

True to his word, Pep came by the next day. He trailer-ed the snowmobile to Vic’s home, handed it over, and never looked back. He never again went snowmobiling or ice fishing. Within days, he had packed up and headed to Florida—determined to leave the ice, the slush, and that brush with death behind him forever.